Contraband Camps

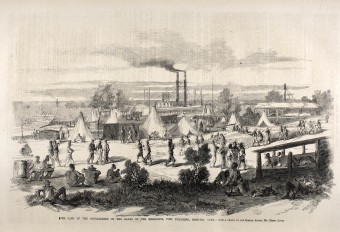

Henri Lovie.

The Camp of the Contrabands on the Banks of the Mississippi, Fort Pickering, Memphis, Tenn, 1862.

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

This illustration, by Cincinnati-based artist Henri Lovie, was published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated

Newspaper in late 1862. The text that accompanied it notes that the “national government” had formed

this camp for men “rescued from slavery” and that “they are employed in labor about the fort…and paid

a pro rata for what they do.”

View Object Details

For thousands of former slaves in Tennessee, contraband camps played an important role in the transition to freedom during the Civil War. The term “contraband,” first applied to runaway slaves in 1861, became a commonly used description of African Americans who flocked to Union lines. After Union forces gained control of West Tennessee in the spring and summer of 1862, many former slaves sought refuge at the army’s camps. In November, near the crossing of two railroad lines at Grand Junction, Tennessee, General Ulysses S. Grant established the first contraband camp in the state that would systematically care for women, children, and men unable to work. He placed Chaplain John Eaton in charge. By war’s end, camps existed near Union military outposts throughout Tennessee.

For men, women, and children, contraband camps were impermanent way stations on the journey to freedom. They carried all the dangers of life within a war zone. Composed of a variety of shelters, often hastily constructed by the residents themselves, some became overcrowded with tragically high mortality rates, and many former slaves avoided the camps altogether. At the same time, camp residents began to establish themselves as free persons, working for the war effort, joining the Union army, attending schools established by benevolent organizations such as the American Missionary Association, holding political rallies and emancipation celebrations, marrying legally for the first time, and establishing churches. Many camps, like those in Memphis, Chattanooga, and Nashville, evolved into postwar African American neighborhoods.

— Antoinette van Zelm, Ph.D., Tennessee Civil War National Heritage Area

Further Reading

- Richard Warwick, “Richard ‘Dick’ Poynor,” in A History of Tennessee Arts: Creating Traditions, Expanding Horizons, Carroll Van West, ed. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2004), 163-164.