Perez Dickinson

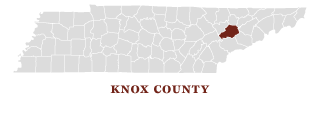

Tennessee was still a fairly young state — the sixteenth state in the Union — at the outbreak of the Civil War, with national aspirations, a strategic location for transportation and an abundance of natural resources. Partnerships formed as northerners moved south. Knoxville, a gateway to the Deep South, had railroad lines coming in from all directions. While prominent Knoxville citizens, many of whom owned slaves, were equally divided regarding secession, the surrounding rural areas of East Tennessee were solidly for the Union.

Auguste Burnard.

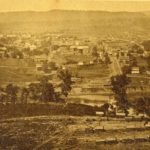

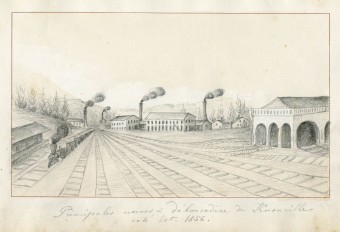

Principales usines & de barcadere de Knoxville cote est. 1856.

McClung Historical Collection, Knox County Public Library

This drawing, by Swiss artist Auguste Burnand, depicts bustling factories and active railroad tracks

in the northern section of Knoxville, where the newly-completed East Tennessee & Georgia Railroad and

the under-construction East Tennessee & Virginia Railroad shared depots and connecting tracks.

View Object Details

Early in the war, Knoxville’s status quo was quickly subjugated by Confederate occupation, which lasted twenty-seven months. Confederate authorities began confiscating the property of advocates for the Union, whom Confederates labeled “alien enemies.” It was a confusing time. One prominent Unionist, Perez Dickinson, a New Englander who had originally come to Knoxville to teach at Hampden-Sydney Academy, owned a prominent mercantile business with his brother in law James H. Cowan. In 1858, Cowan & Dickinson had merged with wealthy Knoxville brothers Charles and Frank McClung. While business partner Frank McClung did not join the Confederate Army, he showed his loyalty to the Confederate cause by assisting behind the lines in the defense of Knoxville. Dickinson, who owned substantial properties and appears to have been a slave owner, ultimately left the city. Other prominent Unionists, such as Robert Houston Armstrong and John J. Craig, also departed, but some, like railroad man Oliver P. Temple waited out the war. Joseph Mabry, another railroad investor, initially paid to outfit a Confederate regiment but quickly changed allegiance when Federal forces arrived. At war’s end, Dickinson and Cowan resumed their partnership with the formerly Confederate McClung brothers and Cowan, McClung & Company became one of the leading businesses in postwar Knoxville.

— Susan W. Knowles, Research Fellow, Center for Historic Preservation, Middle Tennessee State University

Further Reading

- W. Todd Groce, Mountain Rebels: East Tennessee Confederates and the Civil War, 1860-1870 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1999)

- William MacArthur, Knoxville: Crossroads of the New South (Knoxville: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1982)

- Robert Tracy McKenzie, Lincolnites and Rebels: A Divided Town in the American Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006)

- William Rule, ed. Standard History of Knoxville, reprint, with an index by Steve Cotham (Knoxville: Charles A. Reeves, Jr., 2009)